TL;DR:

- Teach problem-solving through engaging challenges in middle school career technical education.

- Daily prompts require students to restate problems in their own words before attempting solutions.

- Shift from large projects to 1 to 2-day mini-challenges, enhancing student engagement and managing activities more effectively.

One of the skills I’ve noticed that many students struggle with is problem-solving. Often, when you give students something challenging they throw either in the towel immediately because it looks “too complicated” or they get so focused on coming up with the “right answer” that they miss the whole process. The best thing for me about career technical education at the middle school level is teaching problem-solving with fun, low-stakes challenges.

When I started teaching career tech, I struggled with getting my students to attempt new things. Most of them had never tried to balance a budget when learning finances or to think about objects in 3D when we started isometric sketching as “engineers.” Since they had limited prior experience, many were overwhelmed and afraid of failing. I had to start by building a classroom where trying and making mistakes is an expectation. I could say a hundred times, “Just try your best!” But so often, the students’ focus was on the final grade, and the prospect of failing can be intimidating.

You also have to be willing to try and fail because I guarantee you're going to have a couple of disasters. Laugh at the mess and try again. Share on XProblem-Solving Always Starts by Asking the Right Questions

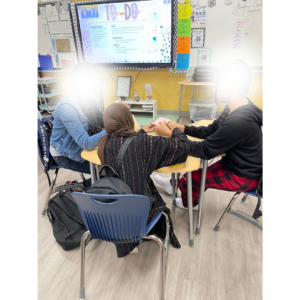

Students working on a design challenge

On Monday-Thursday, my engineering students start class with their challenge journal. (If you are interested in what we do on Fridays, that’s coming in a later post.) The challenge journal prompts are very short questions asking them to sort items, identify patterns, create an algorithm, or create a sketch to solve a specific problem. On many of the questions, we take time to discuss and write the problem they are being asked to solve.

Even though it is in the prompt, I ask the students to write the problem they are being asked to solve in their own words before they attempt to solve it. We do this together for the first few weeks, and then they eventually write it out themselves. Most of the time, when I check journals, I look to see if they restated the problem correctly. Even if their solution isn’t “correct,” they get their points that day for having a solution and a problem statement.

“What’s the Worst that Can Happen?”

I promise you if you want to see the look of terror on an 8th grader’s face, give them something difficult and ask them just to try. My favorite response to their look of fear is usually, “What’s the worst that can happen?” Without a doubt, they ask, “What if I mess up?” I usually shrug and respond, “So? Did you try to solve it? Yes? Okay then, I’m happy!”

Not every attempt is going to work, and sometimes it will be a major flop in those moments we try to laugh and move on. Another phrase I hear a lot is, “This is hard!” My answer to that is, “Yep, keep trying…” Then I always do my best to walk away. I want them to authentically try. If I stay, they will expect me to help instead of continuing to push through.

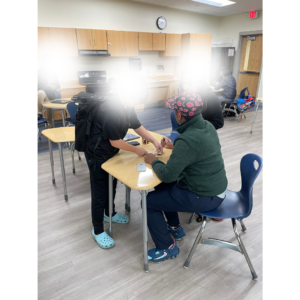

[scroll down to keep reading]Groups or Not?

When I group my students, I always try to have no more than three kids per group. I’ve found that any more than that tends to end up with the students being off-task. I’m just crazy enough most of the time to let the kids choose their groups unless there is an extenuating circumstance. If I want to emphasize communication skills or it’s a more challenging/extended task, I don’t allow solo work. However, I also understand that not everyone works best with others and that forcing kids to work in groups can sometimes cause more stress than benefit.

Building a catapult to defend from a “dragon attack.”

Creating Low Stakes, Fun Challenges

This year, I’ve shifted the focus in my engineering classes from the big projects provided by our curriculum to mini-challenges. This change has made a massive difference in student engagement and buy-in. It’s overwhelming for everyone, including me, to tackle a week-long build project. By days 2 and 3, the students who were only partially engaged are now checked out and creating havoc or ignoring their groups altogether. The students who are on task end up frustrated and arguments ensue. Now, instead of supervising the problem-solving process, I am mediating arguments and putting out fires—figuratively, of course.

By switching to smaller 1 to 2-day mini-challenges, many of these issues are alleviated. Mini-challenges allow me to do this style of activity more frequently. Students who don’t have the stamina to work for multiple days in a row are less likely to get frustrated. Also, I can provide a variety of challenges that will hopefully appeal to most of the students and their strengths. Lastly, it is much easier for me to manage because more students are engaged, and there are typically fewer materials.

Letting Mistakes Happen

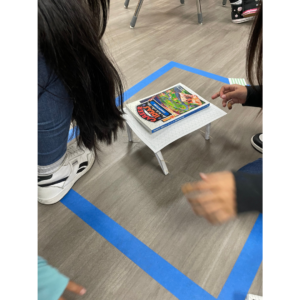

Students building their paper tower.

One of my most recent challenges was a paper tower-building project during STEM week in my Exploring Careers classes. It’s pretty simple for the kids and me. Students get four sheets of paper and 0.5 meters of tape to make the tallest self-supporting tower in 20 minutes. I can quickly scan the room and figure out who works together well, who is struggling, and who has strong problem-solving skills.

This time, I had a pair of boys who didn’t complete the task, wasted their materials, and argued for almost the whole 20 minutes. I spent a lot of time standing in the back of the room watching them as they muddled through and bickered. When the time was up I pulled them to the side. We reflected on what they did during work time and what they should change for the next round of challenges. Even though they weren’t successful on day 1, I was willing to let them try again on day 2’s challenge to see if they could use what they learned to be more successful.

Supporting a stack of books with paper and other items.

Jump In with Both Feet

The best way to try this in your classroom is to jump in! I love seasonal-themed challenges; you can find many for free online. ChatGPT has been very helpful when writing requirements, background stories, rubrics, etc.

You also have to be willing to try and fail because I guarantee you’re going to have a couple of disasters. Laugh at the mess and try again. I always take time to reflect at the end to see if the project met the goals I planned. If not, do I need to make adjustments or scrap it for something new next time? It was a scary jump for me to make, but one I look forward to every time I take it!

About Lisa Jones

Lisa has been teaching middle schoolers in a Title 1 school since 2004. She started her career as an intervention specialist working both in a variety of co-taught general education classrooms as well as in self-contained and content learning classrooms. In 2018, she moved from a co-taught classroom into the world of Career Technical Education and hasn’t looked back since.

Lisa currently teaches an Exploring Careers course for 7th grade and her district’s first-level engineering course, Design and Modeling, for 8th graders. These classes include a wide variety of students including beginning-level English language learners, a variety of students with disabilities at all levels, the “typical” general education student, and gifted students. She’s a big believer in hands-on real-world experiences for students to help them see the world beyond the classroom.

On any given day her students can be learning how to read a pay stub or using paper airplanes to reinforce measurement skills. To prepare every student with skills that will carry them through adulthood, Lisa’s focus this year has been to build problem-solving and communication skills. Her goal is to provide as many unique opportunities for her students as possible so they can see the opportunities that are available to everyone. If asked she’ll tell you that, “if you had told me years ago that career tech would be my jam I wouldn’t have believed you but now I can’t imagine doing anything else.”