TL;DR:

- Shift the focus to the development of skills. Content is still important, but it’s just not the purpose of the course.

- Develop a framework and common language to use during the feedback process.

- Limit feedback to a specific part of the assignment.

- When used appropriately, whole class feedback is a valuable tool.

- Provide multiple practice opportunities to every student for all the skills we are developing.

The last year and a half of school has been challenging to say the least. It’s been challenging for teachers, students, parents, and administrators. There has not been one group that has escaped the impacts of hybrid or remote instruction.

One thing is abundantly clear to me though. People experienced this time very differently. I saw some thrive, while others found the environment to be extremely difficult personally, academically, and emotionally. As this school year approaches or in some cases has already started, it is hard not to think about the potential disruptions that may occur, the students that thrived online and are experiencing anxiety about returning to the building, the students that weren’t served well by remote/hybrid instruction, and the impacts these factors will have on the upcoming year.

It is teaching the students in front of me and having them leave the course with more skills and knowledge than they entered with. I am not preparing them for what’s next. I am teaching them how to learn. Share on XHow do we manage that? I’m going to approach it by leaning heavily on social emotional learning practices and equitable assessments. I know it sounds like a lot of buzzwords, but there are ways to seamlessly construct your course upon these principles. Focus on skills over content, provide descriptive feedback only, and differentiate.

But content is important.

Of course, content is important. It is the vehicle through which all things in class are taught. One of the challenges of making content explicitly important is the reliance on everyone entering the class with the same experience from their previous courses.

In the best of times, this was a faulty notion and it’s even more so now. To exhibit a high level of understanding of the content, students need to possess the skills to apply and communicate that content. Centering content does not provide students who have not yet acquired these skills any chance to practice and develop them. This would require students to either put in work outside of class time or continue to struggle through the course.

Shifting the focus to the development of skills can alleviate some of this burden by eliminating arbitrary deadlines. These skills spiral through the entire course, so the learning doesn’t stop at the end of a unit. There is just new content to use as a vehicle.

So how did I decide what skills to focus on? I asked myself, what are the things you want your students to be able to do? Construct an explanation? Solve a problem? Write a conclusion?

These skills are some of the things that I explicitly value.

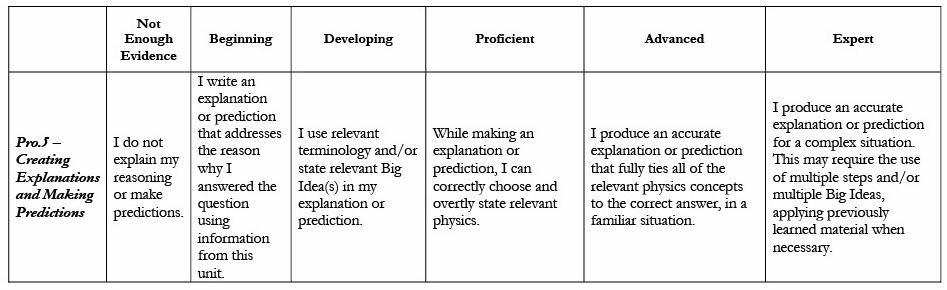

It doesn’t diminish the importance of content at all because to do any of these things well, students must acquire a certain degree of content knowledge. For instance, look at the learning progression below. As students progress through this rubric, the level of foundational understanding must improve.

At the proficient level, students are explicitly stating these concepts. As they move to the advanced level, they have acquired an understanding that allows them to apply these concepts accurately. When a student has mastered this skill, they understand how multiple concepts intertwine. Content is still important. It’s just not the purpose of the course.

Using Descriptive Feedback

The effects of evaluative vs. descriptive feedback are well documented, so I won’t try to make the case for descriptive feedback here. Instead, let’s look at some approaches that make providing descriptive feedback more manageable. After all, one of the biggest deterrents to using descriptive feedback is the time it takes.

Developing a framework and common language to use during the feedback process has helped cut down on the time required. Each skill that we are developing has its own specific language, like the learning progression you saw above. This language is used for all communication in the classroom, whether it’s teacher-student or peer interactions.

Although it takes some time upfront, teaching students how to use this language to provide guidance to their classmates will pay dividends in the long run. It enhances the quality of collaborative work and provides another layer of support for students.

Limiting Focus

Another approach that has helped is limiting my feedback to a specific part of the assignment. For instance, if we were performing a lab investigation, I might tell the students that we are only focusing on the conclusion this time. They would continue to practice writing up the entire lab, but the feedback they receive would only be on the conclusion.

This works for a couple of reasons. First, the turnaround time is greatly reduced, meaning that students get more immediate feedback. The other benefit is that we are not overloading their brains, especially in the earlier stages of skill development. It can be daunting for a student to look at all the changes they must make the next time they do a similar assignment. As they gain proficiency in these skills, we can start to expand our focus.

Whole Class Feedback

When used appropriately, whole class feedback is a valuable tool. As students are developing skills, there are a lot of common misconceptions. Rather than writing the same feedback 20-30 times, I show exemplars or worked examples and discuss the common misconceptions. Sometimes I use tools like Pear Deck and have students critique anonymous work using our feedback framework.

We also do weekly checkpoints, which are like quizzes with a few distinct differences. Students take roughly 15 minutes to complete them, but the checkpoints aren’t collected or scored. The entire checkpoint is reviewed as a class. I show examples of responses at the different developmental levels. Students make notes about what was done well and what they should keep in mind the next time they see a similar style prompt. However it is approached, the feedback has the same purpose. Moving students to higher levels of sophistication through a strengths-based mindset.

[scroll down to keep reading]

Differentiation

I’ve heard the statement “meet students where they are” a lot. What people are really saying is to differentiate your instruction to support every student. Often when we think about differentiation, the image that pops into our minds is every student having a modified assignment based on their needs. This can become completely unmanageable on top of robbing students of an opportunity to challenge themselves and grow.

Over time, I have shifted my view on this. I now view differentiation as adjusting support as opposed to opportunity. I try to make as few decisions for students as possible, so I no longer decide what they can try and what they can’t. Instead, I now provide multiple practice opportunities to every student for all the skills we are developing. Through informal conferencing and class discussions, I provide suggestions and guidance as to what I think might be the best use of their time based on what I have observed. Students are still free to choose though, and I help them develop the skill they’re focusing on at that time.

Final Thoughts

Everything we’ve seen over the past year and a half is not a result of COVID. These challenges existed long before hybrid teaching. However, without our normal interventions that mask their impact, they’ve just become too glaring to ignore.

My approach to the upcoming school year, as is my approach to every school year, is to create a sustainable learning environment that is accessible to all students, provides transferable skills, and values their experience. It is teaching the students in front of me and having them leave the course with more skills and knowledge than they entered with. I am not preparing them for what’s next. I am teaching them how to learn. The rest will take care of itself.

About David Frangiosa

Dave is a high school science teacher from Northern NJ. He’s been performing action research on grade reform since 2015, leading to co-authoring the book Going Gradeless. He is an educational blogger and podcaster, hosting From Earning to Learning. Dave has also presented at numerous local, regional and national conferences.