TL;DR:

- Providing student feedback is a valuable tool that doesn’t need to be overwhelming.

- Evaluate when individual feedback is needed and when it can be taught to the whole class.

- Focus feedback on certain skills.

- Create a framework for feedback that allows students to self-reflect and utilize peer reflections.

- Make feedback meaningful by using descriptive feedback rather than evaluative feedback.

Provide students with actionable feedback. If you’ve been anywhere near a school the past few years, I’m sure you’ve heard this. The challenge is most educators have not been provided the tools necessary to make this an effective and sustainable practice. The importance of descriptive feedback has been well documented for decades.

So why is this still so challenging to implement on a broad scale? The two most common objections to moving to a feedback-centered model I’ve encountered are it takes too much time to provide descriptive feedback, and the students don’t read the feedback anyway. While these are valid concerns, they are not insurmountable.

Feedback Takes Too Much Time

There is no denying that writing comments on every submission for every student on a teacher’s roster will take an extraordinary amount of time. However, there are ways to approach feedback that aren’t as daunting. When structured properly, whole class feedback can be highly effective. During the developmental stages of a new skill or when moving to a more sophisticated level of an existing skill, students are going to have similar challenges. Rather than addressing these challenges individually and writing the same comments dozens of times, review the work with the entire class.

Provide examples of high-quality work, but also show work that has common misconceptions. These samples can be teacher-made or anonymized student work. Students should be active during this time. They could be either annotating their own work or engaged in an interactive technology that would allow them to critique the work being presented. Guide them in this process and reinforce the language that will be used to communicate in the course.

Every aspect of the course needs to reinforce the value of both giving and receiving feedback. The goal is for everyone in the class to make everyone else in the class better, including the teacher. Share on XLimit Focus

It is not always necessary to provide feedback on an entire assignment. In some cases, providing too much feedback can be overwhelming to a student. When a student looks at a large volume of corrections that need to be made, they may not know how or where to start. And the feedback will not have the desired impact. This is especially true during the earlier stages of development.

There are a couple of ways to approach limiting focus, which can vary based on the time of year or level of proficiency. For instance, if students were practicing writing essays, I might tell them that we are focusing on the introduction. Then I only provide feedback on that portion of the essay for their first submission. In subsequent submissions, we could provide feedback on developing supporting details or writing a conclusion. As students gain proficiency, they can request feedback for a specific part of the essay. This provides them the space to grow, while gradually shifting them towards independence.

Peer Feedback

Creating a culture of feedback requires more than just teacher-student interactions. To make this a reality, every aspect of the course needs to reinforce the value of both giving and receiving feedback. The goal is for everyone in the class to make everyone else in the class better, including the teacher. Taking the time to create a framework that will allow students to productively communicate about coursework with their peers will be time well spent.

Provide students with the language necessary for these discussions, and model how to use it. Just like any other skill, this must be explicitly taught and practiced. However, once this becomes part of the course dynamics, students will naturally start using learning language in all their interactions. This will lead to them self- or peer-correcting many misconceptions and asking the teacher for more targeted feedback.

But They Don’t Read the Feedback

I am in complete agreement that it takes way too much time to provide descriptive feedback if students aren’t going to read it and do something with it. That’s why it’s so important to create an environment where this type of feedback is prioritized. To do so, we must understand the different types of feedback.

Evaluative feedback is any judgment on the quality of the work. This can come in the form of letter grades, percentages, or statements such as “well done” or “good job.” This type of feedback was referred to by Ruth Butler (1987) as ego-involving, as it judged a student’s performance on a task.

Task-involving or descriptive feedback focuses on the work alone with no reference to the level of performance. For instance, instead of saying “good job” on a conclusion for a lab investigation, the feedback could be, “The claim clearly states a relationship between two variables. This claim is supported by evidence collected during the investigation. The conclusion would be stronger if there was reasoning that ties the claim to relevant concepts.”

This type of feedback does not allow for ranking and sorting, eliminating the ego. Does this sound familiar? “I did that. I wrote descriptive feedback, but all the student did was look at the grade and put the paper away.” When evaluative and descriptive feedback are combined, the evaluative feedback is prioritized by most students.

Creating a Framework for Feedback

There are some conditions that need to be met for descriptive feedback to be a cornerstone of any course. First, students must be able to understand and apply the feedback. This can be accomplished by creating specific language designed around learning targets. Then, they need to be shown how to use it and given time to practice. Finally, it needs to be separate from evaluative feedback.

Making It Student-Friendly

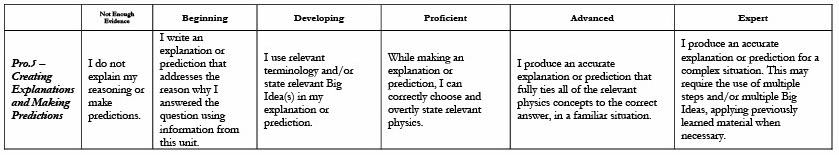

What is it that students should know and be able to do? These are the learning targets for the course. Once learning targets are established, try to identify the discreet steps needed for students to meet those expectations. A shift that has served students well was moving towards learning practices and transferable skills. This doesn’t diminish the importance of content, as content knowledge is required to move to higher levels of proficiency. It does, however, create a framework that lends itself well to descriptive feedback. Take the example for Creating Explanations and Making Predictions.

Figure 1 – Going Gradeless (2021), Corwin Press

There is a progression through the learning process that we can use to coach students to higher levels of sophistication. There is individualized feedback that can be presented, regardless of where a student is entering the progression.

Using the Framework

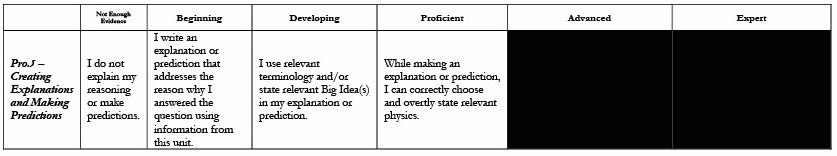

The goal is not to overwhelm students with all the things that they need to do to become an expert. It is to merely provide them the guidance to advance one level of sophistication. For that reason, we only reveal our targeted level of development at that point in time, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Going Gradeless (2021), Corwin Press

All feedback is given from a strengths perspective. These are the positive qualities of the work and here is what can be added to make it even stronger. If we are coaching a student from the developing to proficient level in this learning progression, the feedback provided may be along the lines of, “The explanation addressed the question citing relevant concepts from the unit. What would make this explanation even stronger is if those concepts were explicitly defined.” There is no judgment. It is a clear statement about what is done well and how it can be improved.

It is important at this time to allow students the opportunity for more practice and continue this cycle. This is one of the benefits of an assessment model designed around educational practices. The practices are present in every unit and the feedback cycle can extend through the entire school year. Students will be able to try, revise, and try again many times throughout the course of the year.

Separating Evaluative and Descriptive Feedback

Not every teacher has the ability to remove the evaluative feedback. There are districts that mandate a certain number of grades per week or quarter. This can make the use of descriptive feedback more challenging due to the fixation of many students on that evaluative feedback. One strategy that can be beneficial is to delay grading.

When work is submitted, return it with only the descriptive feedback displayed. Have students respond to the feedback or revise their work prior to providing the grade. By delaying grading, you are eliminating the competition from evaluative feedback. Students have no choice but to look at the comments if they want to evaluate their work.

[scroll down to keep reading]

When possible, remove the grade from the learning process entirely. I know this may make some uncomfortable, but it is worth considering. In the action research we performed for Going Gradeless, the overwhelming majority of students reported that removing grades shifted their focus to learning for the sake of learning, regardless of whether or not they liked grades being removed. This was consistent with what I observed as well. Students were asking more questions about how to improve their skills and knowledge as opposed to raising their grades.

Going gradeless is essentially delayed grading over a much longer period of time. This doesn’t mean that students will never receive a grade. Most teachers are still required to convert all the evidence collected during the learning process to a grade in one form or another. However, this evaluative feedback does not occur until the end of the learning process and doesn’t interfere with the descriptive feedback.

Final Thoughts

Feedback plays an important role in the development of students. The type of feedback and nature in which it is provided can positively or negatively influence many aspects of a student’s education. I have seen firsthand how using solely descriptive feedback can reduce undue stress on students, improve their confidence and self-esteem, and ultimately lead to improved learning outcomes.

For teachers, there may be some obstacles that make this more challenging. However, the benefits to both you and your students will be well worth the effort. For administrators, I ask that you examine the structures and policies of your district and work to remove the obstacles that are inhibiting a culture of feedback.

About David Frangiosa

Dave is a high school science teacher from Northern NJ. He’s been performing action research on grade reform since 2015, leading to co-authoring the book Going Gradeless. He is an educational blogger and podcaster, hosting From Earning to Learning. Dave has also presented at numerous local, regional and national conferences.