TL;DR:

- Assessment should be a series of events, each leading to the next moment of improvement.

- Reimagine assessment by determining what you value and seeking assessment that leads to instruction.

- Understand that “one and done” is not enough and consider consistency and recency when assessing.

As I am writing this, March Madness is ramping up. It is my favorite time of the year, not just because spring is on the horizon, but because of all of the craziness that comes with college basketball’s biggest tournaments. Each year, the NCAA selects 68 teams to participate in their winner take all, national champion crowning tournament. Some of the teams selected get invitations because of their ability to win their conference tournaments. Others are selected because a selection committee simply believes they are worthy based on “the body of their work.”

What makes March truly a month of madness is that nobody really knows who will win it all, let alone any individual game.

The selection committee ranks each team based on their subjective interpretation of who is “better” and then creates a bracket that allows the “best” to play the “rest.” Yet there has never been a year where the “best” (aka the higher-ranked teams) have ever unanimously beaten all of “the rest”…not even on a single weekend of the three-week tournament, let alone the duration of the entire event.

That’s right. In a tournament that lasts three weeks, there has never been a single week in which all of the higher-ranked teams beat those teams predetermined to be “not as good.” It’s complete madness and a gambler’s paradise. Unfortunately, many of us in our schools do something similar, gambling on our own students.

Support your students constantly. Push them to keep growing. Focus on the focus. And remember that three in a row is a step in the right direction. Then we can work on the rest of our ranking madness. Share on XIn many of our schools, March also signals the beginning of a time of madness.

If you are in a high school, students may be fighting for their class rankings. They may be hoping to earn the right to be valedictorian. Or they may be hoping to earn their spot on stage as one of the “top 10” students. In some schools, these students are selected by what some believe to be a “quantitative” measure. Student G.P.A.’s are stacked against each other and those students with the best grades get better rankings.

In some schools, a grade is impacted by more than just academic mastery of content. Some teachers embrace a standards-based approach. Other teachers embrace a completion and effort-based approach.

Some teachers believe a grade should serve as motivation. Others believe a grade should serve as communication.

Some schools weigh grades, giving bonus points to students who take college prep classes. And some schools subtract grades from elective classes.

Some teachers allow retakes and redos. And some calculate the majority of a final grade from a final exam.

Some students are given a seat on the stage because they started playing the game of school early on. They started earning points the moment they entered school. Others are rejected because they began to grow into learners later on once they identified their passions, which may or may not align with a college-bound trajectory.

I know of some districts that have students identify their track as early as 5th grade in elementary school or 8th grade in middle school. The students granted the opportunity to be “the best” are given a distinction. And “the rest,” despite their potential growth and improvement, are left out.

Right now in schools across America and the world, some students are beginning to make their plans for college. And some may begin looking at the annual rankings published by the US News and World Report.

Every college and university in America is ranked on this annual list in an attempt to guide students and their parents towards making choices to attend the best schools.

Included in these annual calculations to determine “the best” from “the rest” are factors such as average incoming student SAT score and the percentage of students rejected from admittance. The belief is that “the best” schools have a lot of people wanting to get in. But because they are so good, only a handful are chosen.

Some states have begun ranking their K-12 schools as well. Schools are placed on a continuum and ranked or scored on a comparative letter grade system of A-F. Schools are designated as “Exemplary” or “Failing” impacting housing markets, local economies, teacher recruitment, and in the long run, childhood destinies.

At this time of year, many schools and districts are beginning to recognize their Teacher of the Year. In some places, this is a recognition brought on by nomination. In some places, it is awarded provided based on a resume, a portfolio, or an interview. And in other places, this award is similar to a popularity contest akin to Homecoming King or Queen…or perhaps even a valedictorian chosen by G.P.A.

Tip #1 to Reimagine Assessment: Determine what you value.

The purpose of this post is not to necessarily condemn any of the aforementioned practices. (However, if you really want my opinion, send me a message, I’ll freely share). But instead, it’s to remind us all that the labels, the rankings, and the assessments we provide to others are always subjective in nature. As much as we may want to make our judgments objective and free from bias, assessment never is. When we determine what to score, what to grade, what criteria to use in our matrix, we place value on what we deem as important.

As the year comes to a close, remember that every grade, every ranking, every award given to a student, a colleague, or a staff member this year is a public statement of your values. Make sure you know what you value because others are certainly making their judgments of you based on how you judge others.

35 students in a class. 70 standards to teach. 180 days of school. Teaching is about so much more than the numbers, but the numbers can tell a powerful story.

Many numbers are overused. Scale scores, RIT points, standard deviations, percentiles, percentages, and value-added measures are numbers that are often used as definitive data by those in authority, yet often dismissed by the real change agents working in classrooms. As a result of so many “experts” stepping in to fill the data gap prevalent in so many schools, with numbers that many of us don’t understand, don’t appreciate, and don’t value, we have often oversimplified our own reliance on more readily available data in our own schools.

During the past year, many classrooms adopted pass/fail or credit/no-credit policies in order to ease the burden on both students and staff.

Last spring, virtually every state in America decided to take a pause on end-of-the-year high stakes assessments in favor of focusing more on teacher anecdotal record-keeping and feedback, something many of us have been begging for since the turn of the century.

What we often forget is that the only reason we have high-stakes assessments in our schools to begin with is that many policymakers believe that teachers often struggle to present an honest and reflective picture of student learning and growth when left to their own measures. So they have allocated billions of dollars over the past two decades to have others collect data for them.

The belief is that because we, as educators, are optimistic by nature and we believe in both our abilities to instruct and our students’ desires to improve, we often have a confirmation bias causing us to overinflate our measures of success.

Whether you had a credit/no-credit policy or whether you presented grades based on rubrics, letter grades, or percentiles, I ask you, how certain are you that the numbers assigned to your students at the end of this past school year, based on your own observations and collection of student evidence, are an accurate reflection of what your students know, can do, or struggle with? Or are your assessments and subsequent grades more a reflection of how well your students were able to play the game of school and jump through our predetermined hoops? Do the grades your students are earning now reflect a level of mastery or a level of compliance?

Tip #2 to Reimagine Assessment: Seek assessment that leads to instruction.

It’s fair for me to interject now that I am a firm believer in mastery-based instruction. I believe that standards-based grading is a pivotal component to helping students find maximum levels of academic growth and learning, but that is not what I am advocating for in this post. It may serve as a starting point and building block. But the end result does not have to be a full conversion of your grading scales or report cards.

Simply transferring your letter grades to numbers, checkmarks, stickers, or other arbitrary symbols really doesn’t solve the problem. Instead, the goal is more simplistic, and honestly more difficult and more important. I am seeking an honest and accurate reporting of student learning. I am seeking objective feedback rooted in reliable and consistent evidence. I’m seeking assessment that leads to instruction. And I am seeking an accurate system of collecting evidence. I don’t want just another label-making machine.

Tip #3 to Reimagine Assessment: “One and done” is not enough.

This past school year, many of us attempted to simplify our grade reporting mechanisms. Like with a lot of systems, this spring magnified many of our current inadequacies and struggles. Specifically, one and done is not enough. We often complain when our students are given one test, on one day in March to prove that they are proficient, yet in our own classrooms, we often tell students they have one chance on one Friday to prove they have mastered everything learned during the week.

Administrators preach for students to be given the ability for retakes and redos, yet those same administrators only enter teachers’ classrooms once or twice a year and expect mastery in every domain. One and done is not enough. It’s not enough for those who may struggle; it’s also not enough for those who may demonstrate competency.

Tip #4 to Reimagine Assessment: Consider consistency and recency.

As a former classroom teacher, I was great at rolling out the red carpet on evaluation day and wowing my administrator. As a former student, I was great and cramming the night before a test and earning an A for my effort before quickly purging my short term memory the moment I turned in my test so that I could begin studying for the next game…ahemmm…assessment I would be asked to play.

This is why today I advocate for something I never did as a teacher and was never asked to do as a student. I ask us all to reconsider our one and done approach to grading, to assessing, and to demonstrating mastery. Today I beg teachers to expect consistency and reliability by playing Tic Tac Toe with evidence collection instead of using a one-and-done approach like we see during March Madness.

Assessment should be a series of events, each leading to the next moment of improvement.

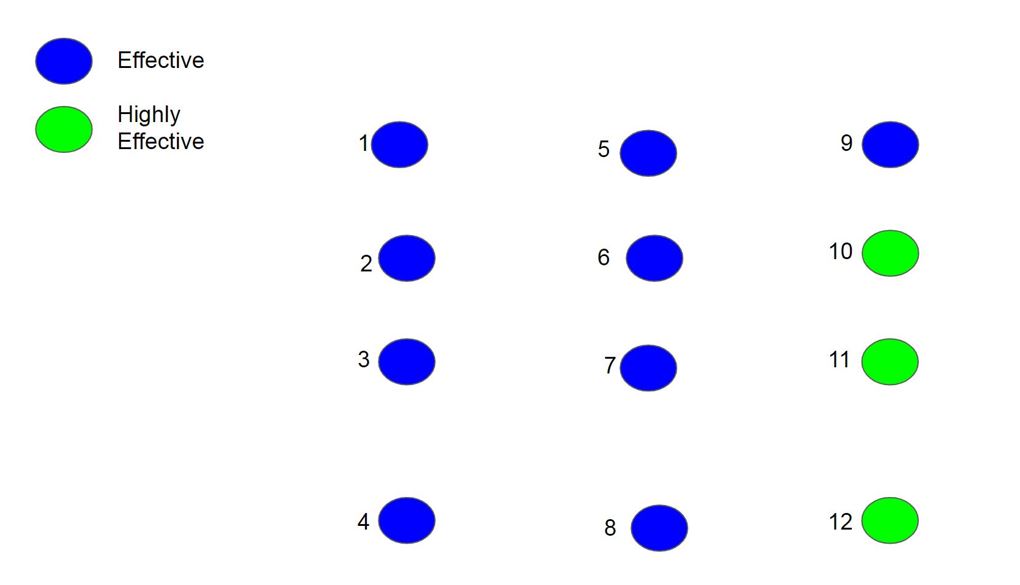

Assume for a moment that this year, as a classroom teacher, you were observed twelve times by your administrator. This is your assessment of job performance. The first nine times you were observed you were scored “effective” (this is like a 3 out of 4 on a rubric). After each observation, you were given feedback and coaching so that by the end of the year, your last three observations consistently resulted in “highly effective” (4 out of 4) ratings. If you were my teacher, and I were your administrator, at the end of the year, your overall designation would be “HIGHLY EFFECTIVE.”

My job is to help grow teachers, to help each improve his/her practice. By the end of the year, you have shown consistency in responding to the feedback provided. So using observations from the beginning of the year against you, before my incredible coaching and teaching were provided, just wouldn’t be fair. I would never advocate that I needed to use the mean and just “average” your scores. Using the mean is just mean. Similarly, simply stopping by your classroom once during the school year would not give me a complete picture of your growth and skills.

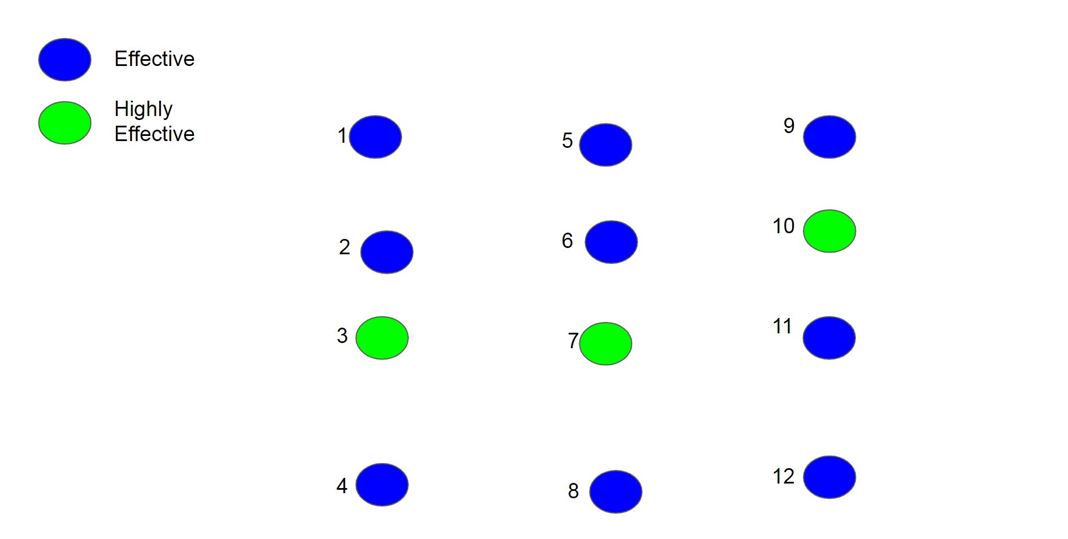

Now, take a look at the image below. Using the same premise, this time you still have three observations identified as Highly Effective and nine as Effective during the school year. But should I draw the same conclusions about your final designation? Have you mastered teaching this year? I would argue, no.

There is no consistent pattern. There is no frequency of the results. And there is no evidence that what was taught actually endured. Yes, you have three Highly Effective ratings, but they are sporadic and inconsistent. Yes frequency matters, but so does recency and consistency.

This same mindset can be used when evaluating student evidence.

I am a huge proponent of using rubrics and grids to guide student evidence collection. I believe doing so allows each assessment/assignment to be used as a diagnostic to help with future planning and instruction. The question that always comes up though is, “how many times should a student have to prove he/she can do something to get credit?” I say three.

If in your classroom you are not comfortable using rubric-driven assessment so you give a more traditional paper-pencil assessment/assignment to measure student learning, how many questions must a student answer to prove he/she understands a concept? Should they answer ten questions? One hundred? All the odd-numbered questions? How about all the even? How many do they need to get correct? Is it 60%, 80%, 100%? If a child can answer nine out of ten, why did they miss one? Does that one matter? When we try to use percentages, we lose out on amazing opportunities.

If I were to give students problems to do in a math class, I would tell my students, “As soon as you answer three in a row correctly, you are done.”

For some students, this may be the first three questions they answer. For others, they may need more feedback, guidance, and practice. These students may need twenty or thirty attempts before getting three in a row. Both are great as they show consistency and recency. Both sets of students are masters.

If you embrace the concept of spiraled assessment, perhaps you believe that a student must show 80% accuracy on any given assessment to show understanding. When you give future assessments, bringing in historical assessment items (again…go read this post for more information), and asking them to demonstrate that they have maintained this knowledge, three more times, would be great evidence.

[scroll down to keep reading]Perhaps you are assessing using multiple methods and tools. Students may present their evidence through a project, a test, a debate, a paper, a collage, etc. To help increase your trust in the assessment and to bring about more validity to your inferences, asking students to use three different methodologies during any given unit, marking period, or lesson may give you greater confidence that students understand the topic.

I have shared this methodology with literally thousands of educators. The vast majority think it makes so much sense. The greatest barrier is always the question: “But how does this get translated into a letter grade?”

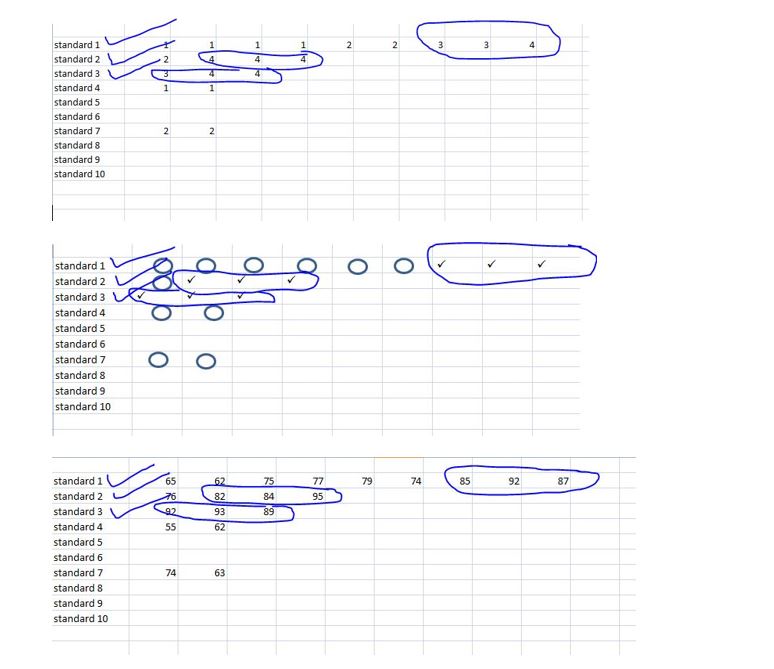

Trust me, I get the reason behind the question, and I have written a lot about this topic. For now, though, a great starting point is to simply get a sheet of paper for each student you teach (this may require an entire notebook in high school). Put a child’s name at the top of the page. Down the left-hand column, simply list the essential standards you are going to teach this year. Make a grid.

Each time you assess a student on a standard, identify whether or not the student was a master. You can do this with a score of 1, 2, 3, 4. You can do this with a checkmark. Or you can do it with a percentage. Once you get three in a row…you’re done. That child is now a master. Move on. Teach something new. Focus on advancement. Celebrate success.

Regardless of whether you have your students in person, face to face, or are teaching remotely, regardless of whether you use standards-based grading or use traditional points and percentages, I challenge you to find a way to make your feedback as accurate as possible.

In our classrooms, grades are simply a shorthand approach to offering the feedback we value. Don’t allow a one-and-done approach to determine success or struggle. Support your students constantly. Push them to keep growing. Focus on the focus. And remember that three in a row is a step in the right direction. Then we can work on the rest of our ranking madness.

Click here to see the full blog series!

About Dave Schmittou

Entering his twenty-first year in education, Dave has earned a reputation for being a disruptor of the status quo, an innovator, and a change agent. Having served as a classroom teacher, school-based administrator, central office director, and now professor of Educational Leadership, he often uses real-life stories and examples of his own life and career to describe why and how we need to confront “the way we have always done it.”

He has written multiple books, including “It’s Like Riding a Bike: How to make learning last a lifetime”, “Bold Humility”, and “Making Assessment Work for Educators Who Hate Data but Love Kids”. He speaks, consults, and partners with districts around the country and loves to keep learning and growing.